What Alaska Can Learn from Northern Sweden’s Clean Industrial Transformation

Launch Alaska Chief Policy & Partnerships Officer Penny Gage (at left) participates in a Fulbright Arctic Initiative fellowship in Luleå, Sweden.

This fall, I had the opportunity to spend two months in Luleå, Sweden (“Lew-lee-oh”), hosted by Luleå University of Technology as part of the Fulbright Arctic Initiative, a two-year fellowship program that brings together scholars, practitioners, and policy leaders from across the Arctic to collaborate on shared research questions related to energy, community well-being, security, and resilience. These topics also drive our work at Launch Alaska. So, during my exchange, I focused on connecting the dots, understanding how Northern Sweden has become a global hub for clean industrial development, and what insights might translate to Alaska.

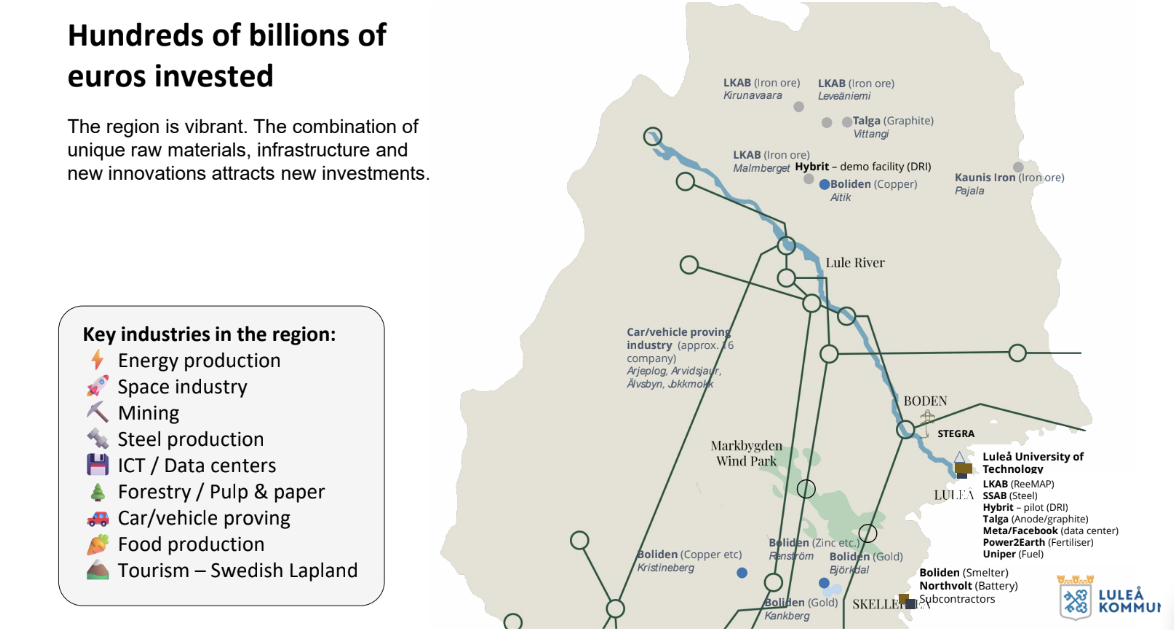

A historic surge of industrial investment is transforming Northern Sweden, from fossil-free steel production to advanced battery materials. More than $110 billion in projects are planned or underway through 2030, positioning the region as a global hub for clean industry while creating tens of thousands of jobs and strengthening Sweden’s economy.

I arrived in Luleå asking this question: How did a remote Arctic region become a magnet for industries of the future, and what lessons could Alaska apply as we pursue our own energy and economic transformation?

What I found was not a perfect model, but a region pushing forward with clarity, coordination, and long-term commitment. Northern Sweden’s experience offers lessons for Alaska not only in what to emulate, but in what foundational conditions must be in place to ensure growth is sustainable and broadly beneficial.

Why Luleå? A Region Transforming at Historic Scale

Northern Sweden offers a rare combination of assets that make large-scale clean industrial development possible: abundant and cheap renewable electricity from hydropower, access to critical minerals, ice-free ports and rail infrastructure, and a strong national industrial policy framework. These factors have attracted major investments in fossil-free steel, battery manufacturing, and advanced mineral processing, alongside a growing ecosystem of suppliers, research institutions, and technology companies.

While today’s investment wave points toward clean industry, Luleå’s economic foundations were built on traditional iron ore and steel production, anchored by the SSAB steelworks and regional mining supply chain, which established the industrial ecosystem that now supports transformation.

One early signal of this transformation came in 2012, when Facebook opened its first European data center in Luleå. That investment demonstrated that the region’s clean electricity, grid reliability, and cold climate could support energy-intensive operations at scale. In the years since, industrial momentum has accelerated, supported by coordinated public planning, long-term infrastructure investment, and a willingness to treat clean industry as a strategic national priority.

The story I observed during my fellowship is not about a single sector or flagship company, though there are bright spots. It is about how Sweden has built durable systems that allow multiple clean industries to develop in parallel.

Three Lessons for Alaska

1) Predictable, low-cost clean energy unlocks industry

The foundation of Northern Sweden’s clean industrial growth is access to reliable, low-cost electricity. The Lule River hydropower system alone generates roughly 10 percent of Sweden’s total electricity, providing a stable backbone for emerging energy-intensive industries such as steelmaking, mineral processing, and manufacturing.

Companies are willing to commit billions of dollars because they trust the region’s energy future. Alaska has similarly strong clean energy resources and potential, but we lack the policy certainty, long-term planning mechanisms, and grid modernization needed to translate those assets into a durable competitive advantage for industry.

2) Coordination matters

A defining feature of Northern Sweden’s industrial transformation is the degree of structured coordination across sectors and institutions. In Luleå, this is exemplified by the Luleåmodellen, a collaborative planning framework initiated to optimize electricity network expansion in support of industrial transformation.

Under this model, local energy companies, municipal authorities, national grid operators, and industrial actors meet regularly to share data, refine demand forecasts, and agree on coordinated infrastructure sequencing. By replacing fragmented assumptions about future electricity load with transparent, jointly vetted projections, Luleåmodellen helped free up network capacity and align grid build-out more cost-effectively with actual industrial needs.

This approach does not eliminate difficult tradeoffs or infrastructure constraints, but it does reduce uncertainty and prevent over- or under-building critical systems. For Alaska, where grid limitations, long timelines, and capital costs already shape what is possible, a similar form of structured, multi-stakeholder coordination could help better navigate long-term infrastructure decisions and reduce friction between utilities, communities, regulators, and industry.

Coordination alone, however, does not resolve the social and cultural tradeoffs that accompany rapid industrial change.

One of the most important lessons I heard came from conversations outside of Luleå, including in Jokkmokk, an inland, largely Sámi indigenous community closer to several proposed industrial and energy developments. Leaders there emphasized the importance of being clear-eyed about the tradeoffs that accompany new industries, even when those industries might use innovative technologies or be less carbon intensive.

New industrial activity there brings real pressures: increased demand on housing and local services, competition for land and water, impacts on Sámi reindeer herding and other traditional livelihoods, and long-term changes to community character. Clean industry does not automatically mean low-impact industry, particularly in rural and Indigenous communities that already carry the cumulative effects of past development.

The takeaway from Jokkmokk was not opposition to industrial development, but a call for honesty and foresight. Communities need time, capacity, and real decision-making power to weigh benefits against costs, understand what is being asked of them, and negotiate outcomes that reflect local priorities. Rushing development without addressing these realities risks eroding trust and undermining the long-term success of even the most well-intentioned projects.

For Alaska, this lesson is especially relevant. As we explore new industries, whether in critical minerals, clean energy, or advanced manufacturing, we must be transparent about tradeoffs from the outset and ensure communities are partners in shaping development, not just recipients of its impacts.

3) Shared roadmaps accelerate deployment

Another enabling factor has been Sweden’s use of shared, sector-led planning processes. Through the Fossil Free Sweden initiative, more than 20 industrial sectors developed bottom-up decarbonization roadmaps, with government acting as a facilitator rather than a central planner. These roadmaps helped industry articulate infrastructure needs, align with national policy, and reduce uncertainty around capital-intensive investments.

Alaska’s energy, industrial, and transportation sectors could benefit from similar cross-sector planning efforts that establish a long-term vision, align public and private investment, and guide infrastructure development in a way that reflects Alaska’s unique geography and communities.

Strengthening Startup Ecosystems: A Model Worth Examining

My research also examined Sweden’s approach to innovation and startup company support. Sweden has been particularly effective at helping new companies get their first customers through structured collaboration with large industrial firms and public entities, public investment vehicles that provide early-stage capital, and long-term funding for incubators and applied research institutions.

These mechanisms complement Launch Alaska’s own work helping startups find customers and deploy projects in Alaska. They demonstrate how public investment, when aligned with real industrial demand, can catalyze private capital and accelerate technology deployment.

What This Means for Launch Alaska and Our Partners

My exchange in Luleå directly informs Launch Alaska’s work going forward.

For our programs and partnerships, this includes strengthening relationships with Swedish incubators, applied research institutions, and universities; exploring collaboration opportunities for future Tech Deployment Track participants; and bringing insights into workforce, minerals, and permitting initiatives relevant to Alaska.

For our policy and advocacy work, this includes applying lessons from Swedish permitting reforms, supporting the development of cross-sector roadmaps that align government and industry priorities, organizing learning opportunities for Alaska leaders, and sharing insights with statewide coalitions and policy partners.

A Final Reflection

Living in Luleå with my family for two months, meeting with researchers, touring steel plants and data centers, talking with startup founders, and seeing massive industrial sites rise from the ground, offered a window into what is possible when a region commits to a shared vision.

Sweden’s path is not without challenges. Workforce shortages, demographic pressures, Indigenous rights conflicts, and political headwinds are real and ongoing. But the overall trajectory is clear: bold industrial action, anchored in clean energy and long-term planning, can transform a northern economy.

Alaska has the resources, the people, and the creativity to build our own version of this future, one that honors our communities, creates good jobs, and strengthens energy resilience statewide. Launch Alaska looks forward to working with partners across the state to help make that future real.

Tack så mycket, thank you very much, for the opportunity to share what I learned.

Penny Gage is Chief Policy and Partnerships Officer at Launch Alaska.